Recently, source code for the Internet of Things (IoT) botnet malware, Mirai, was released on hack forums. This type of malware was used last month in an historic distributed-denial-of-service (DDoS) attack against KrebsOnSecurity, which was estimated to have sent 650 gigabits per second of traffic from unsecured routers, IP cameras, DVRs and more to shut down the domain. Thanks to DDoS prevention measures by engineers at Akamai, the company protecting Krebs, the attack was unsuccessful; however, they report that this attack was nearly double the size of the largest one they’d previously seen.

Now that this malware is released publicly, we can expect to see more DDOS attacks coming from botnets such as unsecured routers and other IoT devices. For those wondering who would leave the default firmware username and password on their devices, the answer is “millions of people.” In fact, using Telnet alone (TCP/IP protocol for remote access), Mirai-author, Anna-senpai, reported “I usually pull max 380k bots.” It’s worth noting that many are saying Mirai wasn’t the only malware variant involved in the attack. Level 3 Communications reported that the Bashlight botnet may have played a part, as well.

How the Mirai attack worked

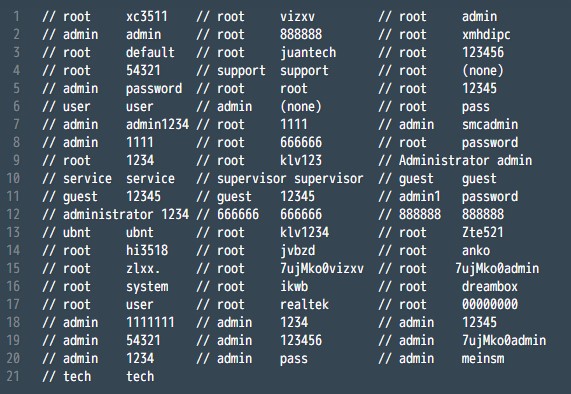

Mirai continuously scans the internet for IoT devices and logs into them using the factory default or hard-coded usernames and passwords.

Once infected, the devices connect to command and control servers to gather details of the attack and target. They then produce large amounts of network traffic—spoofed to look legitimate—at the target servers. With hundreds of thousands of these running in tandem, it’s not hard to shut down most sites. These devices-turned-botnet will still function correctly for the unsuspecting owner, apart from the occasional sluggish bandwidth, and their botnet behavior may go unnoticed indefinitely.

Infected systems can be cleaned by rebooting them, but since scanning for these devices happens at a constant rate, it’s possible for them to be reinfected within minutes of a reboot. This means users have to change the default password immediately after rebooting, or prevent the device from accessing the internet until they can reset the firmware and change the password locally. If you’re taking these steps, make sure to no longer use Telnet, FTP, or HTTP, and instead use their encrypted counterparts SSH, SFTP, and HTTPS.

The underlying problem is that IoT manufacturers are only designing the devices for functionality and aren’t investing in proper security testing. Right now, it’s up to the consumer to scrutinize the security on any devices they use. In the future, some kind of vendor regulation may be necessary.

Hack forums have removed the published code, but it’s still available here.