I’ve worked in the security industry for nearly five years, and it was apparent early on that the most successful people in this field bring to their work a passion and a commitment to protecting not only one’s customers, but to providing a certain level of information about security threats to the world at-large, so even your non-customers can help or protect themselves.

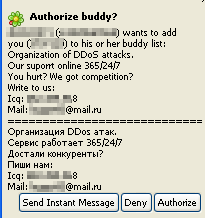

It can be hard to know where to stop once you get on a roll. Malware infections frequently lead to unexplored, interesting backwaters on the Internet. And, sometimes, those backwaters are where the criminals run those operations. When I stumble upon a criminal network or a botnet controller, it simply doesn’t feel like I’ve done enough when I merely add signatures which block or remediate infections and communications with a command-and-control server from Webroot customers. If malicious behavior depends on one or more Internet sites that send instructions, my (and many others’) initial reaction is we need to shut that down, permanently. But sometimes, a too-rapid reaction can blow back in your face.

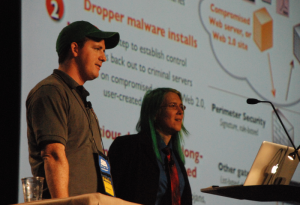

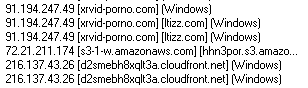

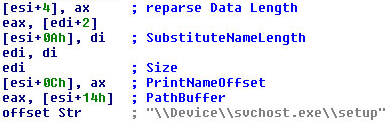

Obviously, that was also the case when Alex Lanstein and Julia Wolf of internet security firm FireEye stumbled upon the Rustock botnet. At one time, before law enforcement in several countries swooped in on the data centers hosting the botnet’s command-and-control (CnC) infrastructure in a coordinated raid earlier this year, the massive network of Rustock-infected computers was responsible for about half of spam flooding the ‘net. The researchers’ instincts to engineer a takedown of the botnet sounded very familiar, but their initial attempts to do so backfired, and may have even spurred the malware developers to change their game, and may have made it more difficult, eventually, to eliminate the CnC altogether.